Reviving Harlem’s Disappearing Queer Spaces

Disappearing Queer Spaces, a book you co-authored while studying at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, was the starting block for the new app. What do you hope to get from shifting to an interactive app-based format?

AA: A Walking Trail with members of the existing queer Harlem community was always something we wanted to do. An interactive app helps bridge past and present, immersing people into experiences and memories in a more accessible way. Now, folks can literally walk in the footsteps of queer predecessors, seeing the streets of Harlem in a new way with augmented reality.

What first inspired you to explore the history of queer spaces in Harlem?

AA: My graduate program had a commitment to celebrating and amplifying marginalized, diverse voices. Through our Disappearing Queer Spaces research, we found that a huge amount of queer Harlem history, especially during the Harlem Renaissance, is tied to buildings that have been demolished and forgotten over time. The app is one way to bring this rich Black, queer history back to life and rebuild a collective memory.

Since this project is about spatial storytelling, give us a glimpse into one of your favorite stories revealed in the app.

AA: In the 1930’s Map of Harlem Nightclubs by Elmer Simms Campbell, we see one unapologetic instance of queerness: Gladys Bentley at the Clam House on Jungle Alley. She was outwardly gay, known to wear a white suit and top hat with drag queens often dancing on stage behind her. Her performances were well known for their bawdy, raucous humor and blues and piano style. If I could go back in time, I would have loved to have seen her perform live.

TV: I was most struck not by any one story, but by the sheer volume of them. The queer community’s history is often overlooked and is rarely in the public eye. I discovered my community was not a small, hidden group, but a vibrant, diverse scene of individuals with their own unique voices spanning back over a century. It was inspiring to learn that the rich tapestry of ideas and culture that make up the queer community is so much deeper and more complex than I had previously imagined.

Why is this uncovering of history important as an architect?

AA: Most architects like focusing on the future and the next big building. Historic preservation is something every architect can and should practice in some way, even if that just means letting the past inform how we think about, see, and design the world. Also, gentrification played a huge role in the demolition of many of these buildings. Architects should understand where and how we are building and plug into the ongoing fight for equitable spatial preservation.

Thank you for mentioning gentrification. How does inequitable displacement and other current societal issues make this work especially relevant today?

TV: As a Black architectural conservationist, I am deeply concerned about the effects of gentrification on communities of color. Across the United States, we are seeing our communities displaced and the built identities of our neighborhoods erased. This project is an act of protest against injustice. As marginalized communities are forced out of Harlem, this project reminds us that even when everything else is taken away, our voices will always be heard.

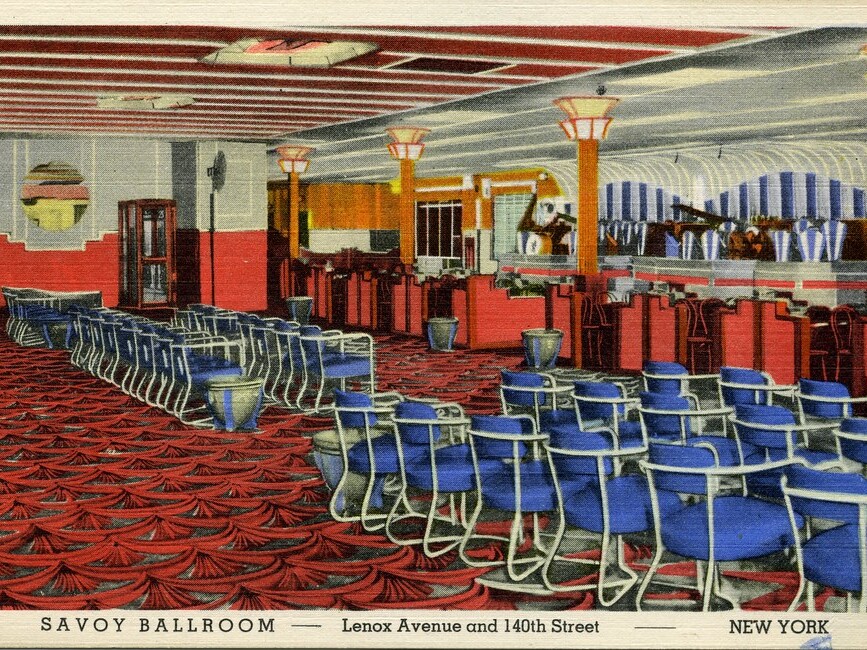

AA: This celebration of queer history is so timely! With heightened political and societal discrimination and violence towards the LGBTQIA+ community – specifically the transgender community – amplifying and protecting voices, histories, and tradition is important. One specific example are recent drag show bans. Many people simply don’t know the beautiful history of drag throughout the United States. Envision drag balls with spectators in the thousands taking place more than a century ago – welcome to the historic Savoy Ballroom. We want this project to stand up against acts of discrimination by increasing awareness and appreciation.

Outside of awareness and allyship, what actions do you hope people who use the app will be inspired to take?

TV: I hope the app inspires people to gain a deeper understanding of their own communities’ histories and to do a little work to uncover the real stories of the people who once occupied the same spaces as they do. Once you find those fragments of history scattered all around you, you find a new appreciation for your surroundings and things that are hidden in plain sight.

AA: There are so many marginalized stories and histories facing erasure. I hope the blending of technology and storytelling in this app inspires others to document and tell them.

Switching gears, tell us about the process of converting the book’s static format to the app’s interactivity.

AA: First, we had to digitally model and texture the historic queer spaces using archived photographs and accounts. Next, we need to marry these new three-dimensional digital models with today’s Harlem streetscape. The first stage of this process is scanning the current buildings, followed by integrating the historic digital models and the present-day scans with specialized software. Then came user experience and app development – Terry’s partnership was invaluable. Finally, volunteers wandered the streets testing the app. Of course, these user tests happened to fall on rainy days!

Any tech tips for our more nuts and bolts readers?

TV: Artificial intelligence was a major contributor to this project. Like many, I was initially wary of this emerging technology. However, I quickly came to realize that AI can be a powerful tool for developers and creative professionals. Much of our code was debugged using AI, which allowed me to quickly find and mitigate problems. We also used AI to create app layout ideas, color schemes, and some texture assets. By understanding how to use AI in my everyday work, I’ve revolutionized my workflow, producing better results in less time.

AA: I’ve learned a lot about app development, photogrammetric scanning, and augmented reality. It’s a giant leap to learn new programs like Reality Capture and Vuforia, but the process of trial and error was worth the results.

Abri, you mentioned the power of collectivity. What partners were important along the journey?

AA: We could not have finished the project or spread the word about it without a community of collaborators including:

- The Queer Students of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation;

- My fellow Disappearing Queer Spaces Authors Rourke Brakeville, Leon Duval, Adrianna Fransz, Ruben Gomez, Kelvin Lee, Jerry Schmit, Brian Turner, Josh Westerman, and Daniel Wexler;

- Andrew Dolkart with NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project was instrumental in assistance with historical documentation;

- And our Walking Tour hosts Build Out Alliance, Harlem Pride, and Save Harlem Now.

Abri will host two walking tours using the newly developed Queer Harlem Renaissance Augmented Reality phone app on May 4, 2024 from 3-5 PM. Contact Abri to sign up.

Read more about DLR Group’s equity commitments and actions. To receive ideas like this directly to your inbox, subscribe to our email list.